Booze, Change, Trails and Telegraph Lines after the purchase of Hudson Bay lands

| Where the info came from |

|

I would like to thank all who sent on information about the Carlton Trail. I got some anecdotal information about the trails near the Iron Horse Trail and I will be looking for more. I received information from Bob Hendricks of Heinsburg who put me in touch with Paul Sutherland, who had done research on trails south of the North Saskatchewan River. These articles have helped sort through the information and develop clarity about the early trails. Information from Kyle Schole, especially the series of township maps from Edmonton to the Saskatchewan border were very useful. Using a simple photo editing program, Adobe Elements, I was able to inspect the consolidated PDF and found 126 township maps with original scan were within Kyleâs map. I was able to break them out as individual township maps and enlarge them. That gave me their dates as well. |

By Marvin Bjornstad

I had for many years an idea that the Dominion Telegraph line followed the Carlton Trail and this was true in some ways, and not in others. Both the trail and the telegraph line changed as a reaction to many events after the mid-1850s, including Confederation, the purchase of the Hudson Bay lands, the spread of smallpox, initial stages of the building of the CPR, and the beginning of settlement. After consulting the article from Paul Sutherlandâs Fort Pitt to Edmonton: the Other Route, the thesis of Alan Ronaghan on The Pioneer Telegraph, JS MacGregorâs Senator Hardistyâs Prairie: 1840/1889 and looking at the Dominion Telegraph booklet, I have put together my information in a new way.

Throughout the 1800s, what was to become the prairie provinces of Canada, underwent rapid changes. Western Canada in the early 1800s had few people of European descent and native people roamed over the land pursuing a nomadic lifestyle. The early days of this century started with a strong competitive and violent fur trade. The merger of the Hudson Bay Company and the North West Company in 1823 ended their rivalry, but many residents were effected by the closing of some trading centers and other independent Metis and American traders soon moved in to be the new competition, many using alcohol in the fur trade. Soon after

Confederation of the Canadian Provinces in 1867, the new government bought out the Hudson Bay Companyâs interest in the vast lands of the prairies. This made Canada responsible for law and order in the new lands, which started with the setup of a new Territorial Government in 1872. The next year increasing violence in the west led to the formation of the NWMP in 1873. The possible sale of the new lands started extensive surveying, starting the beginning of a land rush with 30,000 quarters of land surveyed by 1873. Promises of railways made to entice British Columbia in 1871 to join the federation lead to the development of telegraph lines and planning for the railway.

Changes caused by the Fur Trade

In the early 1800s there was strong competition between the HBC and the NWC for the fur trade in Western Canada. Supplying liquor for furs had become part of this rivalry.

In 1815 John Rowand had a trail blazed on the north side of the North Saskatchewan from Edmonton to Victoria Settlement, to Saddle Lake to Dog Rump Creek House, to Frog Lake and on to Battleford.

In 1823 the HBC and the NWC merged, and it was hoped that this would end the sale of liquor, especially rum, which had become a major factor in the trade. The trade slowed briefly, but independent traders and American competition continued with more alcohol in the fur trade, and the pressure was on the HBC to respond so they did not lose the fur trade.

In the 1850s and 1860s the liquor used in the fur trade which was leading to many problems and deaths, and this again became an issue for various governments. In 1857 the Select Committee in London examined the renewal of the HBC charter with concern for the effect of liquor trade on native peoples in the west. Their conclusion was to renew the charter because a monopoly was more likely to enforce the ban of liquor. âThis did not always sit well with the Metis independent traders who were moving about more of the west.â (MacGregor p )

Expanding the Victoria to Fort Pitt Trail

âYoung John McDougall, still several years away from ordination, stayed with the York boat brigade as far as Fort Carlton where Philip Tate welcomed him while he awaited the arrival of his father and Richard Hardisty. When they came he rode overland with them and reached Fort Pitt in four days. During his ride west of Fort Pitt in August 1862, John fell in love with the terrain.

We rode over the Two Hills [near Tulliby Lake]; we galloped along the sandy beach of

Sandy Lake; we saw Frog Lake away to the right; a few miles farther on we crossed Frog Creek, then Moose Creek, then the Dog Rump.'

During his trip the Reverend George McDougall called at the Reverend Mr. Steinhauer's mission, set his son John and the Reverend Mr. Woolsey to building another at a place they were to call Victoria, and returned to Norway House. After working for a while at Victoria, John went up to Fort Edmonton for Christmas and there he and Hardisty, who was ten years his senior, began what was to be a lifelong friendship.â (MacGregor p 45)

Just as Father Lacombe was about to start a new settlement at St Paul de Cris, Richard Hardisty called for help.

â⦠word came in from Rocky Mountain House that scarlet fever was rampant amongst the Blackfoot. His good friend Hardisty begged him to come to their aid. After Father Lacombe had spent weary weeks ministering to them, spring came, cleansed the camp, and released the weary priest. In April 1865, some thirty airline miles below Victoria, he began erecting his new mission house which he called St. Paul des Cris.â (MacGregor p 57)

As Father Lacombe was planning a new colony at St Paul de Cris, the HBC opposed the plan because they thought it would lead to more use of liquor in the fur trade.

âSuch a settlement of Metis found no favor in the Hudson's Bay Company's eyes. In its train it was sure to bring the same evils that had brought on the Sayer trial at Red River thirteen years previously. Nevertheless, although Metis traders were sure to bring an increased outpouring of liquor, the company had to make the best of a bad situation and endure what it could not eradicate.â (MacGregor p 44)

âIn 1862 Father Lacombe organized a brigade of freighting carts and sent it off to Winnipeg for supplies. Although there was a pack horse trail on the north side of the Saskatchewan River, up to this time no one had taken carts along that portion of it which ran from Fort Edmonton to the site of the modern town of St. Paul. The trail from there east to Fort Pitt had recently received attention from axes wielded by the fathers from Lac La Biche and had been improved until it could accommodate carts. At the same time, those priests cut a new trail from today's St. Paul north to their mission.â [in Lac La Biche]. (MacGregor p 44)

The Victoria Trail out of Edmonton was expanded for carts in 1867 by contract.

âThat, however, was not the only road which the company contemplated at this time. On October 7, 1867, it entered into a $350 contract with J. S. Mead to build a cart road from Victoria post to Edmonton. It was to be twelve feet wide except where it went down to the bridges Mead was to build, where it could be reduced to ten feet.' Undoubtedly this work was to be done on the north side of the river. While for decades men had used a pack trail running along that side of the Saskatchewan, it was only in 1864 that John McDougall had cut a wagon trail from the vicinity of modern St. Paul to Victoria.' Evidently, by employing Mead, this road was now to be completed as far as Edmonton.â (MacGregor p 62)

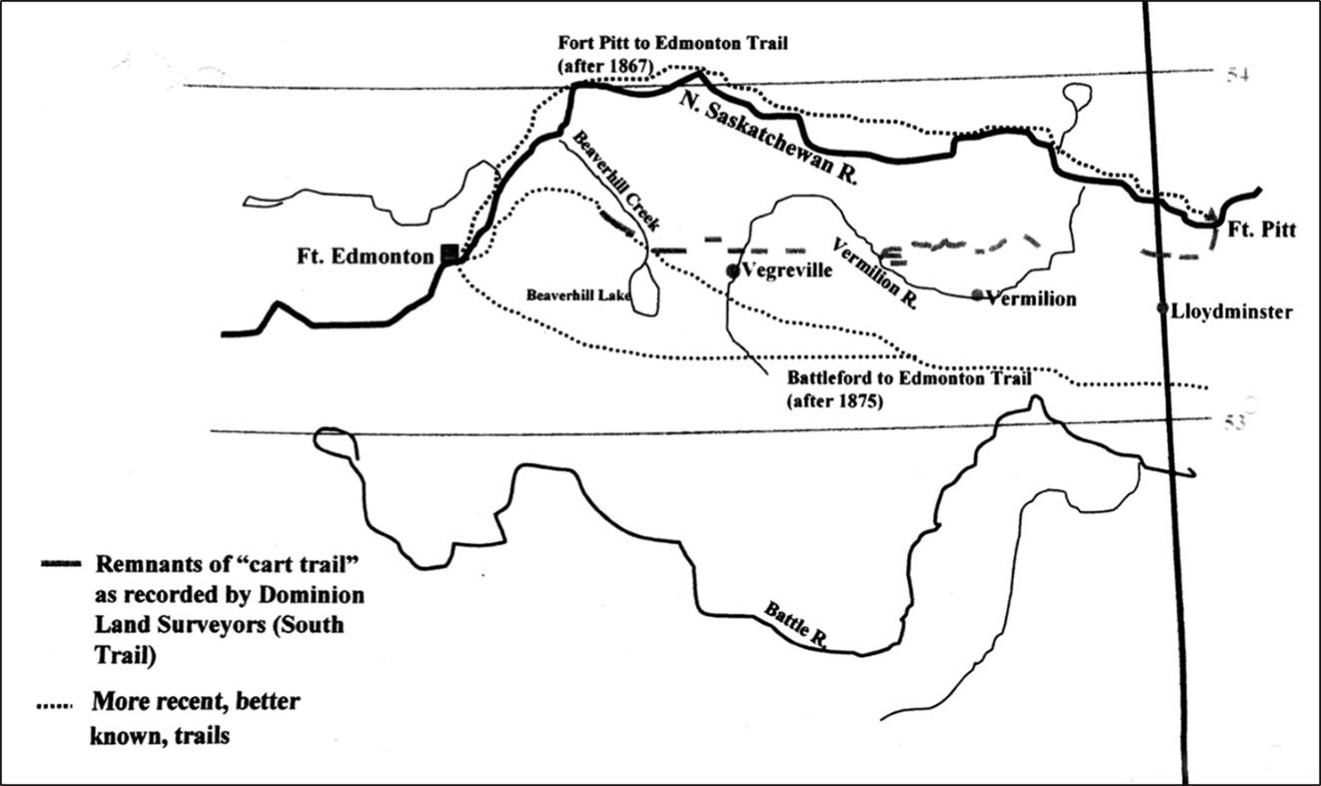

âIn 1867 trader Richard Hardisty was put in charge of a contract with Meade & Company to begin cutting a cart road from Edmonton to Victoria on the north side of the river. (18) In July, 1868, a freight hauler, Phillip Tate, reported that the cart road was now completed. From that point forward, there is no evidence that the HBCo continued to use the southern trail. Perhaps it was occasionally used by others travelling to and from Fort Pitt, but it is likely that the continued aggressive acts by Blackfoot parties would have discouraged this. The route of the Carlton Trail on the north side of the Saskatchewan was now clearly in use. This would remain an important route for several decades as settlers began to put down roots in the area northeast of Edmonton. Evidence of the southern trail route from Fort Pitt west to the Vegreville area soon began to fade.â (Sutherland p 20)

Cart trail south of North Saskatchewan River

In the early and mid 1800s a southern trail was used from Fort Pitt across the parkland area to Fort Edmonton, all south of the North Saskatchewan River. It followed by todays Two Hills to Vegreville. This route was more open and had fewer ravines so was easier to travel. It was however in disputed territory between the Blackfeet and Cree nations. This made it more dangerous.

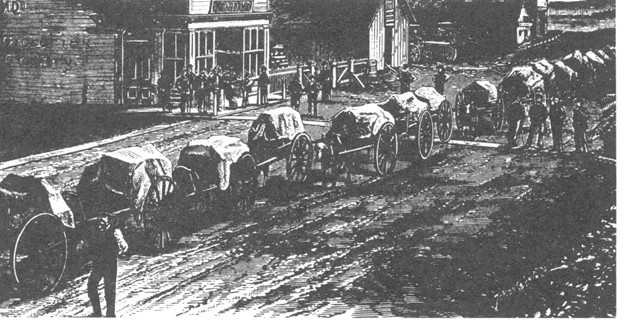

A cart train getting ready to go

âGoods destined for Edmonton were routed through Fort Pitt. In an 1862 Edmonton report, HBCo Chief Factor Christie described the route: "From Fort Pitt to Edmonton 10 days with loaded carts ... Road keeps on the South side of the river all the way to Edmonton."(2)

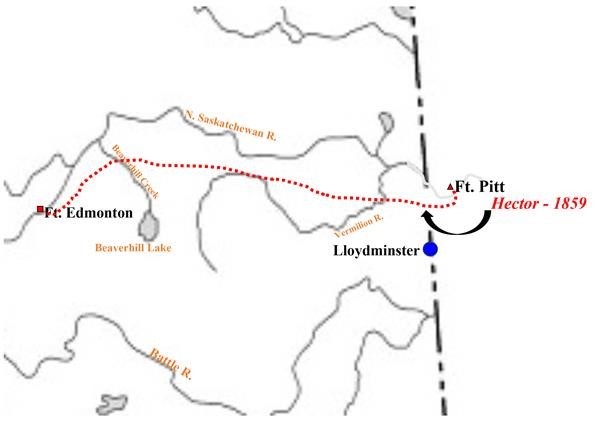

Although during the 1860s the HBCo was the main source of travel along this route, earlier travellers also made use of this trail. On August 4, 1859, when the Earl of Southesk left Fort Pitt for Edmonton he wrote in his journal: "We got the carts and everything across the river...." (3) Since Fort Pitt was on the north side of the North Saskatchewan River, Southesk was obviously planning to take the same general southern route as later HBCo freighters. Even earlier, Sir George Simpson, on his 1842 journey around the world, remarked: "Though we were now on the safer side of the Saskatchewan, in the country of the Crees, (at Fort Pitt, on the north side of the river) yet, in order to save a day's march on the distance between Fort Pitt and Edmonton, we resolved to cross the river into the territory of the Blackfeet...." (4) Simpson's party was travelling on horseback, but they also had a few carts to carry the governor's ample quantities of baggage. However, the most noteworthy cart trip taken on this route, and subsequently mapped, was made by Dr. James Hector, of the Palliser Expedition, in the spring of 1859. The route of the cart trip taken by this hardy and well-known explorer is shown on the Palliser map.â (Sutherland p 20)

Map created by Paul Sutherland from notebooks of Pallister Expedition

âThe use of ox carts to haul goods to Fort Edmonton began in approximately 1861 and continued as the main transportation method until steamboats began to ply the waters of the North Saskatchewan River in 1875. (9) The use of these carts on the southern route between Fort Pitt and Fort Edmonton peaked in 1867 when, according to HBCo records, approximately 200 fully-loaded ox carts used this route.â (Sutherland p 18)

âIn 1864 there were several developments that shed more light on trail usage by the HBCo and others. The well-known missionary, John McDougall, who along with his father, George McDougall, had started a mission at Victoria in 1862, confirmed the poor state of the trail on the north side of the river. In 1864 John McDougall decided to do his own freighting of mission supplies. He made the long trip to Red River (Fort Garry) and returned with a small brigade of carts later that summer. He describes how he was able to follow the regular Carlton Trail route as far as Fort Pitt, continue north of the

Saskatchewan River for another fifty miles, and then: "We were now about fifty miles or more from the new mission, and had reached the limit of wheel-tracks on the north side of the Saskatchewan ..." A few days later, upon reaching the mission, he writes: "Late in the evening of the next day we rolled down the hill into the beautiful valley of the Saskatchewan at Victoria, ours the first carts to ascend the north side of that great river so far west as this point." (12) Obviously there was no established cart trail for the last fifty miles of his journey. It also is very clear, during this period, that the normal cart trail was on the south side of the river and the more forested area north of the river was not particularly amenable to cart traffic.â (Sutherland p 19)

Evidence of cart trail, Paul Sutherland, Alberta History 2012

âThe corridor between Fort Pitt and Edmonton, a fertile parkland area, was considered to be Cree territory. However, the Blackfoot would sometimes challenge this contention and there was often inter-tribal strife as a result. As early as 1845 when Sir Henry James Warre took this route he noted that many people at Fort Pitt were in great dread of the "Slave" (Blackfoot) Indians along this trail. About fifteen years later, when preparing to cross the same area, one of the Overlander parties of 1862 took special precautions, such as keeping their guns loaded and primed at all times. (16)â (Sutherland p 19)

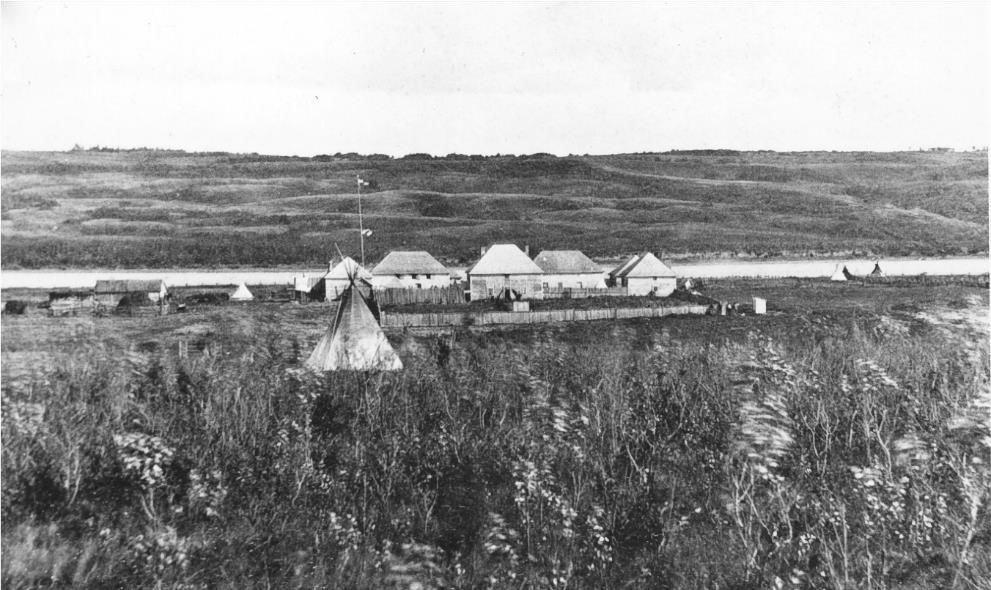

Fort Pitt 1884 Photo by NO Cote, in Paul Sutherland article

âThe HBCo and its employees were normally exempt from aggression by the Blackfoot, but during the 1860s there were several instances where this was not so. In 1866 and 1867 there were a number of serious incidents in which war parties of the Blackfoot Confederacy directly threatened HBCo employees or Metis freemen contracted to the company when they ventured out into the plains south and east of Edmonton. For example, on October 31, 1866, the Edmonton post journal recorded that the Blackfoot stole several cart loads of dried meat and other provisions from a HBCo party and were reported to have seriously threatened the group's lives. (17) However, the Blackfoot seldom crossed to the north side of the North Saskatchewan and both the Crees and the Company felt safer there.â (Sutherland p 20)

âDuring the early and middle 1860s, when HBCo freight traffic was using the southern trail, the carts would first cross the river at Fort Pitt. The freight would be unloaded from the carts, carried over in a crossing boat and then re-loaded on the southern bank. Upon reaching Fort Edmonton the goods were unloaded and again taken across the river to the north bank using a boat.

Beginning in 1866, the company started using a better fording spot than the one directly opposite Fort Edmonton. Carts began to cross to the north side of the river at a point close to the present site of Fort Saskatchewan, just upstream of the mouth of the Sturgeon River. This ford became known as the "Sturgeon River Crossing." In addition to this being a better spot to ford the river, it may also have been chosen to get the cart brigades out of reach of Blackfoot raiding parties for at least part of the trip from Fort Pitt.â (Sutherland p 20)

âThe corridor between Fort Pitt and Edmonton was initially surveyed between 1882 and 1884. The surveyors' observations of trail locations, taken from their field notebooks, have been plotted on a map presented here. The observations show a fairly clear pattern, trail remnants suggesting an east-west trail stretching from the vicinity of Fort Pitt to an area northwest of Vegreville. West of present-day Vegreville there were a large number of other trails identified but the uniqueness of each trail route was lost. For example, several surveyors noted the location of the "Battleford to Edmonton Trail" in that general location but since Battleford came into existence in 1876 it is quite logical for this trail to be noted, for in the 1882 to 1884 period it would have been used accommodate frequent traffic between those two important centres.â (Sutherland p 20) Sale of the HBC

âAbout this time, the great British bankers, the Barings, had joined forces with others and had bought out the original Hudson's Bay Company shareholders. That move was to affect Hardisty's pocketbook and to anger many other company men, but except for that it had no immediate effect upon that company's Saskatchewan District.

The sale of the company to new owners presented its personal problems to Richard Hardisty but they were not so worrisome as was the presence of free traders. The Metis, of course, had been trading for years and some white traders were also working their way west. Even the missionaries, both Roman Catholic and Methodist, had found it necessary to obtain food and services from the natives by bartering. When, however, young David, son of the Reverend George McDougall, openly set himself up as a trader, the company, with its legal privilege of being the exclusive trader in the West, found his action hard to swallow. But as far as the McDougalls were concerned, Chief Trader Richard Hardisty soon found himself constrained to set them apart from the common run of mortals.

However much the company might shut its eyes to David McDougall's illegal trading, it made no pretext of turning the other cheek when Samuel Ballendine Inkster was reported in the Edmonton House journal of January 1, 1867, as openly selling liquor to Indians camped nearby. Moreover, a couple of mining-oriented men by the names of Dan Noyes and "Dancing Bill" were suspected of adding to the company's complications by mixing a little merchandising with their mining. The whole free trade situation had gotten out of hand.â (MacGregor p 57)

âGrowing discontent among both the Metis whom the company employed and those whom it did not was paralleled by increasing distrust on the part of the Blackfoot. In spite of their closer liaison with the missionaries, even the more docile Cree tended to blame white men for everything which annoyed them. And the more the increasing number of traders poured out liquor and the more the company matched their liberality, the worse Indian-white relations became. As for the Blackfoot, who naturally could never reconcile themselves to any white intruders, their dislike, constantly augmented by liquor, kept simmering away near the surface and at times boiled up into troublesome incidents at Rocky Mountain House, Edmonton House, and Fort Pitt.

Like the twisted thinking which is the offspring of all anger, some of the Blackfoot thinking was utterly illogical. In its anxiety to keep peace all around, the Hudson's Bay Company tried to treat all tribes on the same basis and to sell to any who came along. The Blackfoot persisted in distorting this uniform treatment until they came to consider it as favoritism towards the Creeâ (MacGregor p 61)

Groups Passing through area at this time:

- - Captain Palliser - mapping expedition

- - Earl of Southesk - hunting trip

1862 - George and John McDougall-Methodist missionaries

1871 - Sir Sanford Fleming - C.P.R. Survey

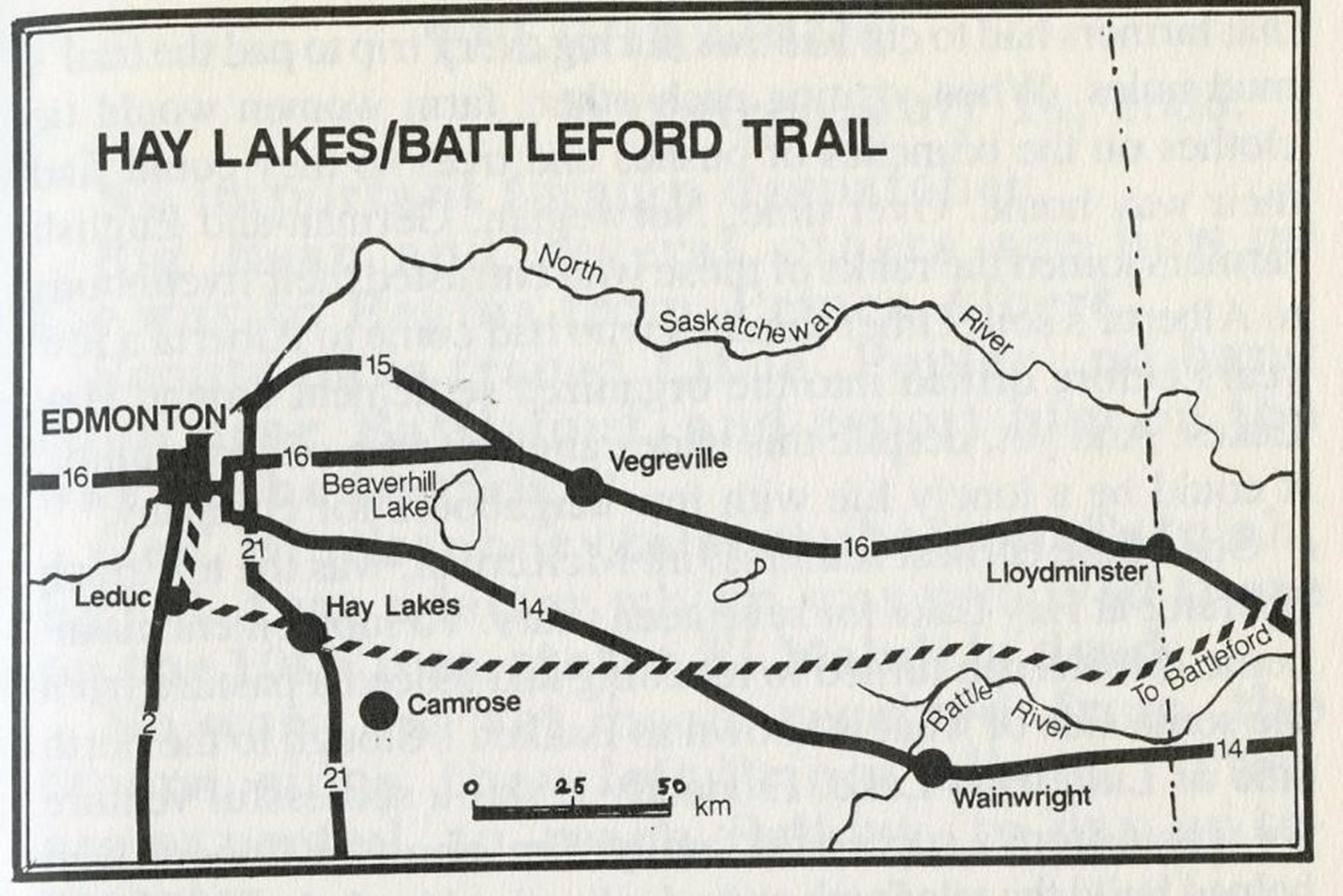

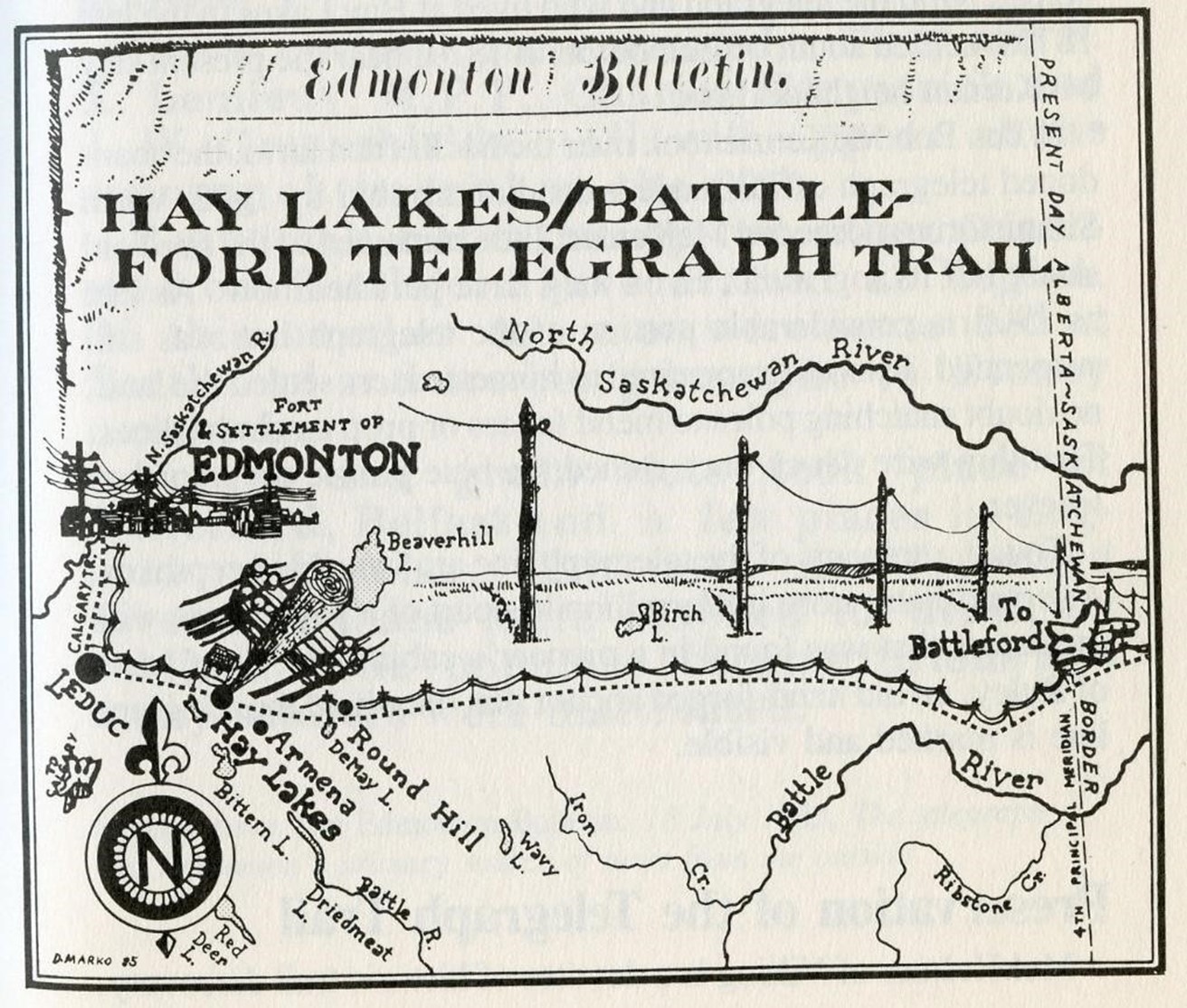

First Telegraph Line Hay Lake to Battleford

The early telegraph line, the Pioneer Telegraph line was started in 1874 to be built as part of the building of the railway. The exact location of the railway was not yet known so numerous Telegraph contracts were undertaken. A Telegraph line was built from Battleford to Hay Lake (south of Edmonton). Although a trail was made along this Pioneer Line, it was seldom used as there was few people living along it. The main use was for maintenance on the Telegraph Line. The line was later expanded into Edmonton.

âMore importantly, the telegraph was instrumental in helping to police the unruly west, notably the Riel Rebellion of 1885. However, in 1887, the telegraph line was re-routed from Battleford to Edmonton along the Carlton Trail via Fort Pitt and Victoria.â (Anderarko, p 44)

âHowever, in the spring of 1885 the telegraph line really proved its worth and the wires were kept hot throughout the period of the rebellion. It was an important factor in the suppression of the disturbance.â (MacDonald, 62)

Ride West of NWMP

âAt Ottawa, cabinet ministers and civil servants alike, confronted with a host of challenges all concerned with setting the new Canada on the road to success, turned their attention to this vexing problem of what to do for the prairies. On the one hand the Indians must be protected, and on the other, Canada must pinch off this nonmilitary but none the less clear-cut American invasion of whisky peddlers. It seemed advisable to follow Robertson-Ross's suggestion and station a small force in the west and to do so quickly. With that in mind, in the House of Commons on April 28, 1873, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald gave notice of a proposed bill to create such a police force.â (MacGregor P 84)

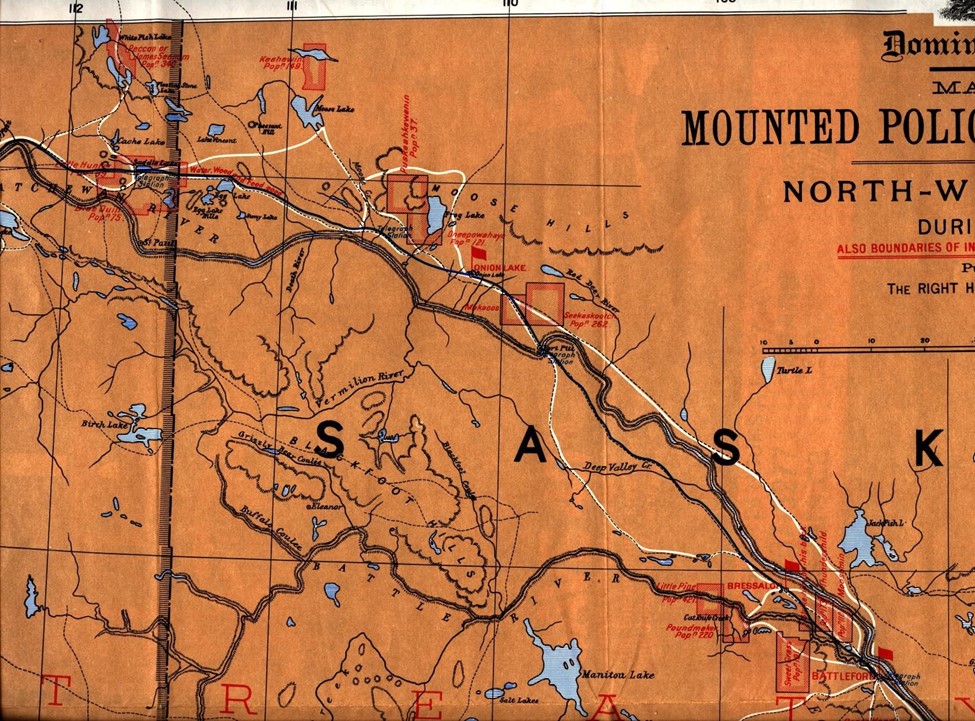

In 1874 the new NWMP was ready to be deployed to bring law and order to the west. The west was changing as the HBC was building steamboats to phase out their long supply lines, Telegraph lines were being built and a new railway was in the planning stages. One group of NWMP marched to the foothills under Major JF Macleod. A second group went north to Edmonton following the Carlton Trail during a wet summer and faced many difficulties.

âWhile Major J. F. Macleod and his men were heading west towards the foothills, another arm of the force under Inspector W. D. Jarvis was making its troubled way along the only well-trodden route to the west, the Fort Garry-Edmonton trail. At Roche Percee the original force had split into two columns, the one continuing towards Fort Whoop-Up and the other, under Inspector Jarvis, bound for Edmonton. On August 1, under the most discouraging conditions and with the youngest and weakest men and the sickest horses, the northerly one started out on its nine-hundred-mile trip. Made up of thirty-two men of all ranks, as well as thirteen Metis driving carts, it crossed the Souris River and struck out to intersect the Edmonton trail at Fort Ellice. With fifty-five sick horses and five in fairly sound condition, seventy-four oxen and cattle, fifty-two cows and forty-five calves, fifty-seven oxcarts and twenty-six wagons, some agricultural implements and their supplies, they finally reached that fort.

On August 18, leaving some very sick men and exhausted horses and most of their cows and calves, Inspector Jarvis and Sub-Inspector Severe Gagnon led their men towards Forts Carlton and Edmonton. From Fort Ellice west, of course, they were on a well-used trail where two or three days seldom passed without some travelers meeting others. The possibility of their overtaking anyone was remote because no other wayfarers would have encumbered themselves with anything but the bare necessities of travel and consequently would have made much better time. Most of the eastbound traffic consisted of traders or Metis taking their robes or dried meat towards Fort Garry.

While the weather was about average for that time of year, it had been a wet season and long stretches of the trail were under water. As various animals fell out they had to shoot or abandon them and from time to time left a wagon alongside the trail. On October 18, for instance, when they were crossing the sand and muskeg stretches east of the Victoria mission, they were reported as making "two miles in the morning. Crossed Mud Creek. One wagon mired so deep it all but disappeared. Eight miles in the afternoon. Three more oxen abandoned, and three wagons far behind. Camped half a mile from Victoria (Hudson's Bay Company post).â

That evening they camped on the old river course north of the settlement, which the Indians called The Hairy Bag, and next morning moved on to the company's little post beside the mission. There Inspector Jarvis arranged with a settler to care for all the cows and calves during the winter, as well as eleven oxen.

There, too, they left several wagons and some flour. Nine days later, with all the horses close to exhaustion, they had difficulty getting wagons across the Sturgeon. One horse, unable to make it, died in the stream. The weather was cold, the trail terrible, with sloughs across it every few hundred yards; men and animals struggled knee-deep in black mud. Time and again the wagons had to be unloaded and dragged out by hand.

Then, as J. P. Turner told of it in The North-West Mounted Police,

Fort Edmonton was now less than a dozen miles away. Darkness fell. In the gloom it was hard to hold the trail . . . . Still they pressed on. At five in the morning Steele called a halt, and they camped at Rat Creek, about four miles from Edmonton. Gagnon had also arrived at this point with two ox teams. All had been on the move for more than 20 hours. Worn and fagged out, men and beasts sagged down to a desperately- needed rest.

Next day the bulk of the cavalcade reached Fort Edmonton where Chief Factor Richard Hardisty proffered every possible kindness. As Inspector Jarvis reported:

I may state that on looking back over our journey I wonder how we ever accomplished it with weak horses, little or no pasture, and for the last 500 miles with no grain, and the latter part over roads impassible until we remade them ....I kept a party of men in advance with axes, and when practicable felled trees and made corduroy over mud holes, sometimes 100 yards long, and also made a number of bridges and repaired all the old ones. We must have laid down several miles of corduroy between Fort Pitt and here . . . . Streams which last year when I crossed them were mere rivulets, are now rivers difficult to ford. And had it not been for the perfect conduct of the men, and real hard work, much of the property would have been destroyed.

So, two weeks after their colleagues in the south had reached the Oldman River, and near physical exhaustion but buoyed up with pride in the stupendous sixty-day task they had finished, the northern wing of the Mounties went into winter quarters in Fort Edmonton.

During 1874 in its westward thrust the civilization to which Richard Hardisty, the McDougalls, and the fathers out at St. Albert had looked forward so eagerly had made long strides. The NWMP had arrived, the Saskatchewan River's first steamboat had fought its way upstream as far as Fort Carlton, and in October 1874 "contracts were entered into for constructing a telegraph line from Red River to Edmonton."26 And the CPR transcontinental was soon to follow.

The prospects for the sparsely scattered settlers along the vibrant North Saskatchewan east-west axis across the prairies were excellent. Even the fact that in its Fort Macleod the southern wing of the Mounties had given that axis a complementary dog-leg along the edge of the foothills added to those prospects. For the old fur traders' capitals, Forts Ellice, Carlton, and Edmonton and their connecting route which by water or overland Richard Hardisty had traveled so often, all was indeed well.

For the natives, however, the prospects were more dubious. Sitting around their campfires at some favorite spots in the valleys of the Bow and the Battle, the Qu'Appelle and the Turtle rivers, the Indians waited and worried. At their tea dances at Buffalo Lake and Batoche, at St. Laurent and the Cypress Hills, the Metis, too, waited and wondered.â (MacGregor P 110 - 113)

Patrol Map of NWMP after they arrived in area in 1874

Life after 1885

After the rebellion of 1885 with violent events at Frog Lake, Fort Pitt, Battleford, Steel Narrows, Duck Lake the awakened Canadian government put more effort into the projects designed to settle the west. The Territorial Government moved to Regina, the CPR moved forward to completion, telegraph lines moved to where the population was, and larger waves of settlement began.

âAt the end of 1885 there were some fifty thousand souls in the Northwest Territories; five thousand Mªtis, twenty thousand Indians and twenty-five thousand white folk.' Whereas two-thirds of that population was east of what is now Alberta, the Indians were so distributed that nearly half of them were within the boundaries of modern Alberta. The three populated regions tributary to Edmonton, Calgary (including Red Deer), and Fort Macleod were reported to contain 5,616, 5,467 and 4,450 souls respectively and in each case some 3,000 of these were Indians, leaving whites and Mªtis to make up the remainder.

Consequently, in these three regions with which Dick Hardisty was primarily concerned there were some six thousand white folk. And in contrast to the Indians ever receding farther into their reserves, these six thousand were busily expanding their holdings and their economic base. Some were mining coal, some sawing lumber, some grazing cattle, and some growing grain. Men like Frank Oliver, Dick Hardisty, J. Lougheed, and A. P. Patrick, however, were disappointed in how slow other Canadians were in realizing the opportunities available on the prairies. They knew that with its rich soil alone the West could feed millions of mouths and yet by the end of 1885 so few folk had come to till it.â (MacGregor P 228)

Building of the Dominion Telegraph Line after 1885

After the end of the rebellion in 1885 the prevailing opinion was that better communications in the west was essential. A study had been done in 1884 suggesting the line be moved to where the bulk of population was living in Victoria, Saddle Lake and Frog Lake. In JS Macdonald, a telegraph operator in the area at the time:

âWithout the wire, the condition of affairs throughout the whole northern country would have been absolutely unknown outside, for the Police were too few and too much occupied to establish a patrol to the newly-built railway to the south. Indeed, under the conditions, such an arrangement would have been impossible, and a chaotic state of affairs must have resulted. Police officers, Indian agents and missionaries did splendid work in pacifying and persuading the Indians of many reserves from rising, but lacking the information they received by way of the telegraph, their efforts would have availed but little. A knowledge of the fact that troops were on their way did more to keep the Indians on their reserves than all other influences combined. Indeed, had the rebels possessed a capable leader, the results might have been disastrous, in any case, for it would have been a comparatively easy matter to have cut and carried away sections of the wire, which would have put it out of operation until repairedâa work hazardous in the extreme. The wire was cut on a few occasions, leaving it on the ground, but these were ordinary breaks which were easily repaired by linemen who, however, took great chances of being ambushed. The Rebellion cost the country about 7 millions of dollars, but without the telegraph, it would have cost many times that sum, while the loss of life would have been infinitely greater. From a fairly complete knowledge of the conditions existing at the time, I am convinced that only individual Indians kept the peace from unselfish motives. And, considering the difficulties of the elders in restraining their young braves, for whom war spelt glory and the glittering promises of the rebel leaders, this is scarcely to be wondered at.â (Macdonald, 35)

So the spring of 1886 saw new construction on the cart track north of the North Saskatchewan River that was becoming the main transportation link while the area awaited the coming of river travel using more reliable paddle wheelers which had started trials in 1879. âIn the Fall of 1884 the Department decided to change the route of the line between Battleford and Edmonton. There was at this time no settlement, except at Bresaylor, throughout the district through which the line passed, while Indian Agencies at Onion Lake and Saddle Lake, on the north side of the river, were without communication of any kind. It was, therefore, decided to erect a new line from Battleford, crossing the river at Fort Pitt, with offices at Pitt, Mooswa, Saddle Lake, Victoria (now Pakan) and Fort Saskatchewan. The breaking out of the Rebellion prevented this change being put into effect immediately, the work commencing in the Spring of 1886. Between Battleford and Pitt an innovation was made in that the poles were of iron, hollow cylinders 15 feet high, 25 inches in diameter, with a double ground plate to hold them firmly. The experiment was a thorough success, the poles immune to prairie fires, lightning and other foes of wooden poles, remained in place until the line was abandoned 40 years later. From Pitt to Edmonton the line was built of tamarack poles under the direction of Lineman McKay, with G. H. Clouston, of Battleford, as foreman of the work.â (Macdonald, 45)

So, during the 1800s the Carlton Trail was a main link from Winnipeg to Edmonton. The section from Fort Pitt to Edmonton started as a blazed trail in 1815, opened further by the fathers from Lac La Biche transporting furs in 1862, widened from St Paul to Victoria by John McDougall in 1864, and completed from Victoria to Edmonton in 1867. In 1886 the Dominion Telegraph was moved off the Battleford to Hay Lake trail to become a new telegraph line up the Carlton Trail from Fort Pitt to Frog Lake to Mooswa to Saddle Lake to Victoria and on to Edmonton. This trail continued in use for some time, but now HBC transportation of trade goods was attempted up the river by steamboat in 1879. The pushing forward of improved transportation by CPR to Calgary in 1885, and the new line to Edmonton in 1891 ended the Carlton Trails usefulness except for more local traffic. Even the local traffic lessened as a new rail reached Vermilion in 1905. North of the North Saskatchewan River traffic declined even more as CN rail reached out from Edmonton to St Paul in 1919, and to Heinsburg in 1927. This trail had been a main land traffic road from 1815 to about 1910.

The early residents of Northern Alberta had seen many changes every ten to fifteen years from 1815 to 1910. Their early days saw very few people in a vast empty land. New changes came at them every few years. The fur companies merged in 1823, violence spilled out from the fur and liquor trade in the 1860s, scarlet fever and other diseases flourished, Canada was formed in 1867, the smallpox epidemic of 1870 ravaged the whole countryside, the new North West Territorial government of 1872 brought new changes, the beginning of building of railway and telegraph lines in the 1880s accelerated the flow of people and change, and the formation of new provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta in 1905 resulted in large numbers of new people on the land.

These trails and telegraph lines were very intertwined. Confusion often comes because there were two main trails in operation. The Fort Pitt to Edmonton trail that lasted from about 1860 to 1868. The Carlton Trail in the Iron Horse Trail area, although blazed in 1815 and used sporadically after this, came into main use as the country opened up in the mid 1860s. The initial telegraph line built in 1874 was from Battleford to Hay Lake and later connected to Edmonton. After 1885 this line was moved to run north of the North Saskatchewan from Fort Pitt to Saddle Lake to Edmonton. So two trails and two telegraph lines!

| Today's Iron Horse Trail |

|

Using many maps I was able to make a tracing of the Carlton Trail they reveal on a current printout of the Iron Horse Trail map that covers all 10 municipalities. I have sent on my tracing in the attached document called: Tracking the Carlton Trail along the Iron Horse Trail. It is attached to another page here. |

References

Russell, R.C., The Carlton Trail, 1971. Prairie Books, Western Producer Saskatoon

MacGregor, JG, Senator Hardistyâs Prairies: 1840/1889 Western Producer Prairie Books, Saskatoon Saskatchewan

Ronaghan, Alan, The Pioneer Telegraph in Western Canada, 1976, Thesis submitted to Department of History, Saskatoon Saskatchewan

Sutherland, Paul, Fort Pitt to Edmonton: The Other Route Alberta History Autumn 2012 MacDonald, J.S., The Dominion Telegraph, Canadian North-West Historical Society Publications Vol 1 #VI 1930

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Booze,-Change,-Trails-and-Telegraph-Lines-.pdf | 1.42 MB |

| Carlton-Trail,-Ralph-Russell.pdf | 65.61 MB |